If you’re like me, there are days when you only have 10 minutes to practice bass. Maybe work takes over, maybe family needs you, or maybe you’re simply low on energy. But even on those days, you can still make real progress, if your practice is structured and efficient.

One area I always return to is shape practice: intervals, triads, seventh chords, triad pairs, or small melodic cells. These are the building blocks of vocabulary, fretboard fluency, and ear training.

Here’s the problem: Most musicians practice shapes in only one direction (usually ascending), and only in one position.

But music doesn’t move in one direction. Your lines won’t only ascend. Most importantly, your ears shouldn’t only recognize shapes or intervals when you move “up.”

So I needed a way to practice shapes that:

- deepens my sound understanding

- builds technical fluency

- forces direction changes

- strengthens fretboard awareness

- works even when I only have 10 minutes

A few years ago, I came across a monster of a guitarist Matteo Prefumo. And in his Guitar Scales Book, I noticed that he was really big on practicing vocabulary in ALL directions.

This started my journey with structuring my practice in a more disciplined way, in a way that embodied both a Fundamental Direction and a Global Direction.

Later, this led to me building the Sound & Shape Practice Tracker to help me stay present and focused with this approach to practice.

Below is exactly how I practice shapes on the bass to internalize them faster.

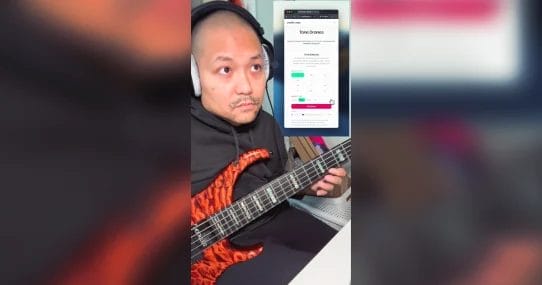

Watch the Video Demonstration

Here’s the full walkthrough showing exactly how I practice shapes using this method:

Fundamental Directions: The Core of the Shape

Every shape can be played in three Fundamental Directions:

1. Ascending

The shape moves upward (e.g., root → 3 → 5).

2. Descending

The shape moves downward (e.g., 5 → 3 → root).

3. Mixed

The shape ascends and descends within the same gesture. This adds contour, musicality, and real-world variability.

These three directions alone expose huge gaps in most players’ understanding of sound. You might ascend a shape confidently—but descending the exact same shape might suddenly feel unfamiliar or unstable.

Practicing all three ensures you truly know the sound, especially if you’re able to also sing the shape!

Global Directions: How You Move the Shape Across the Neck

Once you practice a Fundamental Direction, you then move the shape globally on the fretboard:

- Globally Ascending (shape shifts upward in pitch along the neck)

- Globally Descending (shape shifts downward)

This is crucial.

Because music becomes much more dramatic—and musical—when the shape direction and the global direction are in contrast.

Example:

- Ascending shape + Globally descending

- Descending shape + Globally ascending

This creates automatic tension and release. It also forces your ear to stay alert and internalize the shape independent of position.

Example: Triad Pair Shape Practice

In the video, I demonstrate using:

- C major triad

- D minor triad

Here’s how I walk through the full practice:

1. Ascending shape + Globally ascending

Root position → 1st inversion → 2nd inversion → up the neck

Clear, straightforward.

2. Ascending shape + Globally descending

Ascending arpeggios—but the whole system is moving down the neck. This contrast creates a more dramatic sound.

3. Descending shape + Globally ascending

Descending arpeggios while shifting upward. Another dramatic contrast.

4. Descending shape + Globally descending

Less dramatic—more parallel movement—but still essential.

5. Mixed shapes

For example:

Take one note from the D minor triad, pair it with the C major triad, and create a short melodic cell (A → C major triad). Then move that cell across the neck:

- Mixed shape + globally descending

- Mixed shape + globally ascending

These small cells become expressive, melodic vocabulary.

Reminder: You should be working on singing these exercises before you get caught up on the technical aspects, like fingering. Singing should always come first, because it ensures that you truly know the sound.

Why This Method Works So Fast

Most practice routines focus on:

- fingers

- positions

- mechanics

But the sound has to come first.

Practicing shapes in all directions—then shifting globally—forces your ear to:

- identify a shape independent of pitch

- hear contour changes

- stabilize intervals in both directions

- recognize melodic logic anywhere on the neck

This is the closest thing to “fretboard fluency” training I know.

And when you pair it with technical practice afterward, your hands learn to follow what your ear already hears.

Why I Built the Sound & Shape Practice Tracker

I have a tendency for my mind to wander when I practice. Even if I know the method, I’ll drift, skip directions, or stop short of a full cycle.

The tracker solved that.

It helps me:

- stay present and intentional

- make sure I actually practice all Fundamental + Global directions

- rate my sound familiarity

- rate my technical fluidity

- document progress

- notice gaps

- avoid blind spots

- keep sessions short but effective

And it’s simple enough to use every day.

Try the free interactive version here:

Sound & Shape Practice Tracker →

Apply This With Any Shape

This method works for:

- intervals

- triads (major, minor, diminished, augmented, sus2, sus4)

- seventh chords

- 6th chords

- pentatonics

- melodic minor modes

- diminished / augmented systems

- triad pairs

- lines you transcribe

- anything with contour

Once you know the sound, the fingerings follow naturally.

Take This Further

If you want to turn this into a daily habit and accelerate your internalization:

Use my free Sound & Shape Practice Tracker

It guides you through:

- Fundamental Directions

- Global Directions

- Singing

- Technical work

- Self-assessment

- Daily progress logging

Try the free tool here: Sound & Shape Practice Tracker →

Closing Thoughts

You don’t need long practice sessions to improve. You just need a consistent structure that trains:

- your ear

- your mind

- your sense of movement

- your understanding of shape

- your technique

This method keeps your practice musical, efficient, and rooted in sound.

And with the tracker, you can stay intentional—even with only 10 minutes.

If you enjoyed this method and want to expand your harmonic vocabulary, check out my Jazz Harmony & Shapes category — packed with lessons on triads, triad pairs, chord tones, melodic movement, and improvisational shapes.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly is a “shape” in music?

A shape is a small musical structure—like an interval, triad, seventh chord, triad pair, or melodic cell—that maintains its identity no matter where you play it on the bass. Shapes are the building blocks of lines, harmony, and vocabulary. When you internalize the shape, you can recognize it by sound and reproduce it anywhere on the fretboard.

What’s the difference between a Fundamental Direction and a Global Direction?

Fundamental Direction = how the shape itself moves (ascending, descending, mixed).

Global Direction = how the position of the shape shifts across the neck (upward or downward).

Working both together helps you separate sound identity from location, which is essential for true internalization.

How do I know if I’m actually internalizing the shape and not just memorizing finger patterns?

If you can sing the shape accurately in all directions and shift it globally without losing pitch center, you’ve internalized the sound. Memorizing fingerings alone breaks down as soon as you change keys, positions, or directions.

Can I use this method with scales, modes, and arpeggios?

Absolutely. Anything with contour can be practiced with this method:

– Major scale shapes

– Melodic minor modes

– Pentatonics

– Triads & seventh chords

– 6th chords

– Diminished / augmented structures

– Triad pairs

– Transcribed lines

If it has shape, it can be internalized.

Do I need to sing even if I’m not a singer?

Yes—not to perform, but to train your ear. Singing forces your brain to predict the sound before your fingers play it. You don’t need a good voice; you only need pitch awareness. This is the fastest way to eliminate gaps in your internal sense of shape.

Is this method only for bass players?

Not at all. Guitarists, pianists, horn players, singers, and composers can all use this method. The tracker is instrument-agnostic, and the sound-first approach works universally.

How This Fits the Bigger Picture

This concept lives inside The Posido Vega Method™ — an ear-first framework for building real musical fluency through phrase-based learning and structural hearing.